japanese poetry

Japanese Poetry: A Look at the Art of Words

Savannah Walker

Posted on May 26, 2025

Share:

Japanese poetry has enchanted readers for centuries with its elegance, emotional depth, and vivid imagery. Whether carved into wooden tablets or passed down through song, poetry has always played an important role in Japan’s cultural history.

The beauty of Japanese poetry lies in its ability to express powerful feelings and natural imagery using few words. If you’ve ever wondered about the different types of Japanese poetry, this is your chance to dive in. Let’s explore five well-known forms and see what makes each one so special.

Haiku

Haiku is the most famous form of Japanese poetry, especially outside Japan. It’s known for being short—just three lines—and following a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. Despite its brevity, haiku can be incredibly deep. These tiny poems are often inspired by nature, the seasons, or a fleeting moment.

The beauty of a haiku lies in its simplicity. It often includes a seasonal word, or kigo, which hints at the time of year the poem is set. This seasonal element connects the poem to the natural world and gives it a particular atmosphere. Haiku also typically includes a moment of contrast or surprise, called a kireji, which adds emotional depth. One of the most famous haiku poets is Matsuo Bashō, who lived during the 1600s. His poems focused on travel, nature, and the beauty of everyday life. A classic example is:

An old silent pond,

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.

This short poem paints a vivid picture while hinting at a more profound meaning about stillness and change. Haiku encourages readers to pause and reflect, making it one of the most beloved forms of Japanese poetry even today.

Are you looking for great snacks to enjoy while reading classic Japanese poetry? Check out Sakuraco! Sakuraco delivers traditional Japanese snacks, teas, and sweets from local Japanese makers directly to your door so you can enjoy the latest healthy treats directly from Japan!

Tanka

Tanka poetry has existed even longer than haiku and offers a slightly longer structure. A tanka has five lines with a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable count, giving poets more room to express themselves. The name tanka means “short poem,” but compared to haiku, it allows for a fuller exploration of feelings and imagery.

Tanka was especially popular among aristocrats during the Heian period (794–1185 CE). It was often used in love letters or exchanged between friends. Poets used this form to express personal emotions like love, sadness, longing, or joy, often set against a beautiful seasonal or natural backdrop.

One reason for the tanka’s popularity is its emotional range. Haiku might focus on a moment, but tanka can tell a brief story or offer a complete emotional experience. It’s still widely used today and remains a favorite among both amateur and professional poets in Japan.

Waka

Before the word “tanka” became common, this style of poetry was simply known as waka, meaning “Japanese poem.” Waka was a general term that included various short poetry forms in classical Japanese. It was used for centuries to describe poetry written in Japan’s native language, as opposed to Chinese.

Waka poems typically followed the same 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern as tanka and were often included in imperial anthologies. One of the most famous collections is the Man’yoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), which dates back to the 8th century and features over 4,000 poems by people from all walks of life.

Waka were highly regarded in court life, and composing poetry was considered an essential skill for the nobility. They were often used in courtship and political affairs, with people exchanging poems like we might send a text message today. Waka continues to influence Japanese literature, art, modern music, and theater.

Katauta and Sedoka

Katauta and sedoka are two lesser-known forms of Japanese poetry, but they offer a fascinating look into ancient styles of expression. A katauta is a single poem with three lines in a 5-7-7 syllable pattern. It’s thought to be the shortest of all the traditional Japanese poem forms and was often used as a question or half of a conversation. A sedoka, on the other hand, is made up of two katauta paired together.

This gives the poem a mirror-like structure: 5-7-7 / 5-7-7. It’s believed that sedoka poems were used as dialogues or expressions of shared emotion between two people. These forms were popular during the Asuka and Nara periods (roughly the 6th to 8th centuries) but eventually faded from everyday use. Even though they’re not as widely written today, katauta and sedoka give us a glimpse into how ancient Japanese poets used poetry for artistic expression, communication, and emotional connection.

Kanshi

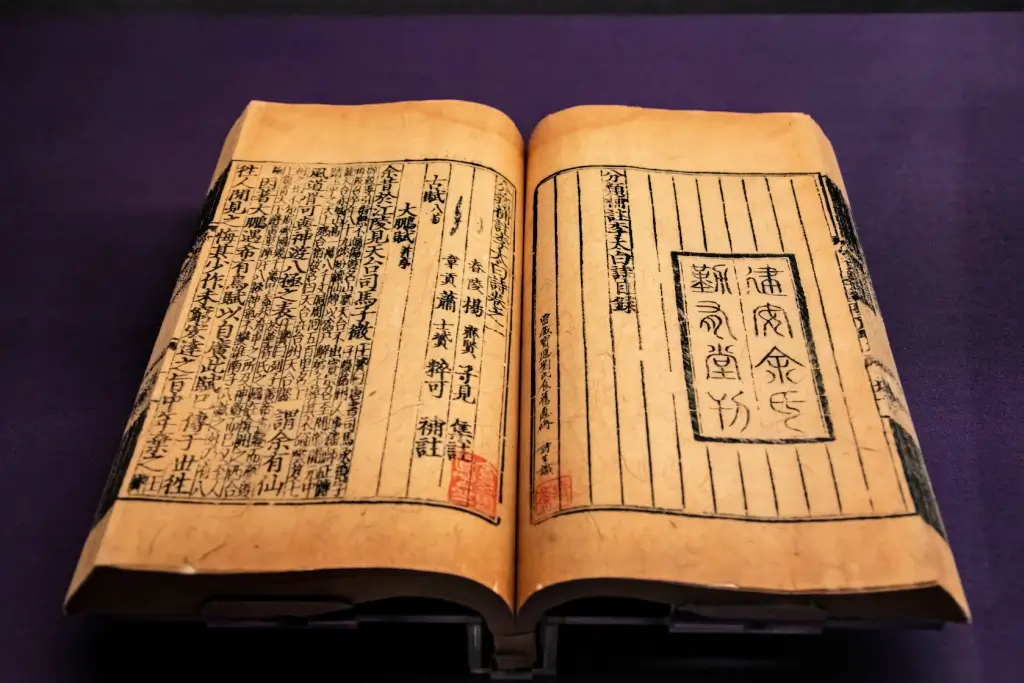

While many Japanese poetic forms developed within the country, kanshi came from outside influence, specifically Chinese poetry. Kanshi refers to Japanese poems written in classical Chinese, often using Chinese characters and forms. This style became popular among scholars and aristocrats during the early Heian period.

Kanshi was seen as intellectual and refined, and writing it required knowledge of the Chinese language and culture. Many kanshi poets were inspired by famous Chinese poets like Li Bai and Du Fu, but they gave the form a Japanese twist, using it to reflect on nature, loneliness, or spiritual themes.

Because of its ties to Chinese literature, kanshi wasn’t as emotionally expressive as tanka or waka. It was often more philosophical or focused on scholarly themes. Although written in another language, kanshi became essential to Japan’s poetic heritage and helped shape the country’s literary identity.

Why is Japanese poetry still so loved?

Japanese poetry continues to be celebrated today in all its forms because of its timeless beauty and emotional depth. Each poetic form—haiku, tanka, waka, katauta, Sedona, and kanshi—uniquely expresses feelings, captures moments, and reflects on nature or human life. Even though they’re centuries old, these poems speak to modern readers with surprising clarity and elegance.

Part of what makes Japanese poetry so captivating is its ability to say so much with so little. Whether it’s a brief haiku about a falling leaf or a tanka that captures the sorrow of a farewell, these poems allow us to connect with the thoughts and emotions of people across time. They invite us to slow down, observe the world more closely, and find meaning in small details.

So, if you’ve never explored Japanese poetry, now’s the perfect time to start. You don’t need to be a scholar or fluent in Japanese to enjoy it—just a little curiosity and an open heart. Who knows? You might even be inspired to write a few lines of your own. Have you ever written this kind of poetry, or have a favorite poem? Let us know in the comments below!

Cited Sources

- Tokyo Weekender. “Japanese Poetry: A Brief Introduction to Kanshi, Waka and Haiku“.

- Nara Prefecture Complex of Man’yo Culture. “Man’yō-shū and Japanese Culture“.

- Sustainable Japan by The Japan Times. “What exactly is waka?“

Discover authentic flavors with Sakuraco

Get Sakuraco

Discover authentic flavors with Sakuraco

Get Sakuraco

Related Articles

Okinawa Locations: What is the Valley of Gangala

Okinawa’s human history stretches back tens of thousands of years, and its lush landscape hides ancient sites where early people lived and prayed. The Valley of Gangala is one of the most fascinating Okinawa locations.

Nara Japan: The 12 Heavenly Generals at Shin Yakushiji

Nara, Japan, is home to some of the country’s oldest and most treasured Buddhist artifacts from the Nara Period.

Jomon People: A Journey Through Prehistoric Japan

If you are interested in history, you may already know that the Jomon Period stands out as a time when people carefully learned to live in close harmony with nature.

Coming of Age Day in Japan: The Ultimate Guide

Coming of Age Day, known in Japanese as Seijin no Hi, is a national holiday that marks the transition into adulthood. It is observed on the second Monday of January each year.